The Other World in Sound

A Dream of Debussy’s Fantaisie

It is vital for my spirit to remain close to what I believe is “God’s” world as I move between realms, this being the world of the classical arts and sciences. Sitting in the box among the keepers of classical music in New York City, I remarked to the man beside me that to remain submerged in the depths of this world feels like an utter dream. He nodded.

The chatter dwindled to whispers as the most magical kind of dusk settled in, accompanied by the native sounds of paper shifting and bows finding their place. A pin dropped. Salonen lifted his baton, and the strings began. It was a night of Debussy and Boulez at the New York Philharmonic. Though I am less familiar with Boulez’s work, the roaring finale just before intermission, strong and charging, was enough to make me erupt in praise, my admiration carrying me all the way into the private lounge, where I managed a single square of cheesecake between introductions.

Of course, it was the second part of the program that excited me most: Debussy’s Fantaisie for Piano and Orchestra. In the lounge, when I mentioned being familiar with it, a senior member of the NY Phil cocked his head, convinced I must be mistaken. Apparently, no one knows this piece. Though I cannot claim it comes to me like the back of my hand, I was certain I’d encountered it on a playlist somewhere, and despite everyone’s doubt, I was right.

The piano solos, fluttering in their dreamy, sylph-like beauty, fit for a forest filled with romance, felt strangely familiar, as if they were the turquoise mist dancing above the lake beside Queen Mary’s rose garden in Regent’s Park last month, off to find its home in another world. My heart lifted with a girlish love and a longing for whatever in the material world might be compatible with such a feeling.

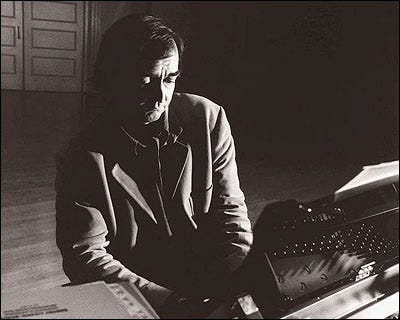

Pierre-Laurent Aimard’s innocent imagination was apparent to me in this world of make-believe. The light melody flowed through his fingers on stage, fluttering. While this might strike some as too coquettish, I reveled in the beauty of it, a sensation perfectly matched to the satin trousers of men playing with angels in the rococo room at The Frick.

Debussy wrote Fantaisie for Piano and Orchestra in 1889–1890, when he was in his late twenties, marking his first steps away from Wagner’s influence and toward new sound worlds such as the Javanese gamelan he encountered at the Paris Exposition of 1889. Unsatisfied with the work, he withheld it from performance and publication during his lifetime, and it was only after his death in 1918 that his friend Jean Roger-Ducasse prepared the score for publication; the Fantaisie finally received its premiere in London in 1919.

After the piece had finished, though the program was not yet over, I sensed Pierre’s presence behind me. He had slipped in through the darkness, dressed in black, his expression still as a timeless painting. I glanced over now and then at the glow from the stage falling across his face.

Backstage, while people mingled, I found myself drawn only to his hands; long, slightly bent, worn with wisdom, their folds deep and striking, shaped by years of expert use. I had not seen anything more beautiful all week. This is saying a great deal, as the night before I had been surrounded by Hong Gyu Shin’s collection, floor-to-ceiling works by Balthus, Wegener, Dalí, and others, while eating rice and seaweed in his bamboo slippers and discussing Victorian London with a British art historian friend.

…Yet it was the hands of Pierre-Laurent Aimard that stayed with me, carrying years, passion, beauty, and a presence that was so strong.

(I am always in awe when offered the hand of a great pianist to shake, Aimard and Kissin the most affecting of them.)